Contents

Hey everyone, welcome to my first ever entry! In this series of posts, I’ll be taking a deep dive into Riemannian geometry by working through John M. Lee’s Riemannian Manifolds - An Introduction to Curvature.

I’ve always wanted to learn about this topic ever since I found out that general relativity makes use of the tools developed in this area. Riemannian geometry also makes its appearance in machine learning through non-convex optimization on manifolds and methods based on the natural gradient, as well as in reinforcement learning with the natural policy gradient. However, I will not get a chance to take the relevant class at Berkeley (boo!) so I’ve decided to learn it myself!

For these notes, I’ll be writing down the most salient points, as well as proofs that I’ve attempted on my own. If you find any errors, please let me know. With that, let’s get started!

Definitions

We begin by defining the additional structure on a general smooth manifold that we will be concerned with throughout our study of Riemannian manifolds.

Definition. A Riemannian metric on a smooth manifold $M$ is a smooth (covariant) $2$-tensor field $g \in \mathcal{T}^2(M)$ that is symmetric and positive-definite.

We refer to $(M, g)$ as a Riemannian manifold. Observe that the Riemannian metric defines an inner product on every tangent space of the manifold. Having this notion of an inner product allows us to define familiar concepts such as norms and angles for each tangent space.

One may ask if Riemannian metrics even exist (of course, beyond the natural Riemannian metric on Euclidean space). The following proposition demonstrates that in fact, every smooth manifold can be endowed with a Riemannian metric.

Proposition. Every smooth manifold $M$ admits a Riemannian structure.

Proof. For every $p \in M$, find a coordinate chart $(U_p, \phi_p)$ containing $p$. Then, we can locally define a smooth $2$-tensor field $g_p \in \mathcal{T}^2(U_p)$ by defining

where $(F_{ij})$ is a positive-definite matrix. With this choice, $g_p$ is symmetric and positive-definite.

Now, observe that since the $\left\{U_p\right\}$ form an open cover of $M$, we can find a partition of unity $\left\{\psi_p\right\}$ subordinate to the cover. Since the support of any $\psi_p$ is contained in $U_p$, $\psi_pg_p$ is a smooth $2$-field on all of $M$, taking $g_p$ to be zero outside $U_p$. Then, define $g$ as

This is a well-defined sum throughout the manifold as the set of supports is locally finite. Furthermore, $g$ is symmetric since every $g_p$ has the same property, and $g$ is positive-definite since every $g_p$ is positive definite and every $p \in M$ is contained in one of the supports.

Thus, $g$ is a Riemannian metric, and $(M, g)$ is a Riemannian manifold.

If we have two Riemannian manifolds $(M, g), (\tilde{M}, \tilde{g})$, as well as a diffeomorphism $\phi: M \to \tilde{M}$, then we say that $\phi$ is an isometry if $\phi^* \tilde{g} = g$. Riemannian geometry is concerned with the study of properties that are preserved under these isometries.

Observe that as a consequence of the symmetry of the metric, we have that in local coordinates,

Derived Metrics

Now that we’ve defined Riemannian metrics, let’s look at how we can derive new metrics from metrics on other spaces.

Induced Metric

Consider a Riemannian manifold $(M, g)$ and an immersed submanifold $N \subseteq M$. Then, we can define the induced metric $\tilde{g}$ on $N$ as the pullback of $g$ under the inclusion $i: N \to M$, i.e. $\tilde{g} = i^* g$. Using the identification of the tangent vectors of $N$ with the tangent vectors on $M$ that are also tangent to $N$, we see that the induced metric is essentially $g$ restricted to the subspace of vectors that are tangent to $N$.

Metrics on Product Manifolds

If $(M_1, g_1), (M_2, g_2)$ are Riemannian manifolds, then on the product manifold $M_1 \times M_2$, we can obtain the natural identification of tangent spaces $T_{(p, q)}(M_1 \times M_2) \cong T_pM_1 \oplus T_qM_2$. Consequently, we can define a natural metric $g$ on the product as

where $X_1, Y_1 \in T_pM_1$ and $X_2, Y_2 \in T_qM_2$.

Covering Metrics

Supposed that $M, N$ are smooth manifolds, and assume that there exists a smooth covering map $\pi: M \to N$. Remember that a deck transformation (on a smooth covering space) is a diffeomorphism $\phi: M \to M$ such that $\pi \circ \phi = \pi$. Then, given a Riemannian metric $g$ on $N$, we can pull back the tensor field onto $M$ and obtain a Riemannian metric $\tilde{g} = \pi^* g$. The metric $\tilde{g}$ is often referred to as a covering metric, and $\pi$ is then a Riemannian covering.

Proposition. The covering metric is invariant under deck transformations.

Proof. Using properties of pullbacks, we have that for any deck transformation $\phi: M \to M$,

proving the desired claim.

The proposition above has the following natural converse.

Proposition. Assume that $(M, g)$ is a Riemannian manifold and $N$ a smooth manifold such that $\pi: M \to N$ is a smooth normal covering map. Then, if $g$ is invariant under all deck transformations, then $g$ descends to a Riemannian metric $\tilde{g}$ on $N$.

Proof. Let $p \in N$. Since $N$ is evenly covered, there exists an open neighborhood $U_p \subseteq N$ of $p$ such that every component of $\pi^{-1}(U_p)$ is diffeomorphic to $U_p$ through $\pi$. Choosing one of these components $V$ amounts to a choice of section $\pi^{-1}_V$ of $\pi$. Define the Riemannian metric locally to be $\tilde{g} = \left(\pi^{-1}_V\right)^* g$. To see that this is well-defined, consider another component $V’$. Then, since the cover is normal, there exists a deck transformation $\rho$ taking $V$ to $V’$. Since $g$ is invariant under all deck transformations,

Thus, we have a well-defined Riemannian metric on an open neighborhood of every point. These local metrics agree on overlaps, and thus by the gluing lemma, we obtain a global Riemannian metric $\tilde{g}$ on all of $N$.

Constructions

Let’s look at what we can do once we have a Riemannian metric on a smooth manifold.

Raising and Lowering Indices (Musical Isomorphisms)

A Riemannian metric allows us to convert tangent vectors into tangent covectors and vice versa. For any $p \in M$ and $v \in T_pM$, we can obtain a covector $v^\flat$ by defining

In local coordinates, we can write this covector as

We have, in effect, lowered the index $i$, thus the name (and the flat notation).

Naturally, we can ask if an inverse operation exists. First, observe that the action of lowering an index is linear, given by the positive-definite matrix $(g_{ij})$. Thus, if we let $g^{ij} = (g_{ij})^{-1}_{ij}$, then for any $p \in M$ and $\omega \in T_p^* M$, we can define a tangent vector $\omega^\sharp$ as

Thus, the operation corresponds to raising an index, and thus the sharp notation.

To see the importance of the ${}^\sharp$ operator, recall the gradient of a function $f$ as defined in a standard multivariable calculus class, which is a tangent field defined on all of $\mathbb{R}^n$. Although the differential $df$ of a function $f \in C^\infty(M)$ is naturally a covector field, we can extend the concept of a gradient field to an arbitrary Riemannian manifold by letting $\nabla f = df^\sharp$.

Note that the idea of lowering and raising indices can be extended to higher-order (mixed) tensors.

Inner Products of Tensors

As defined above, the Riemannian metric gives us an inner product on each tangent space. In fact, the Riemannian metric gives rise to an inner product on tensor bundles as well. Given a tensor bundle $E$ on $M$, a fiber metric on $E$ is a smoothly-varying inner product on each fiber.

Lemma. Let $g$ be a Riemannian metric on a manifold $M$. Then, there exists a unique fiber metric on each tensor bundle $T_l^kM$ with the property that if $(E_1, \dots, E_n)$ is an orthonormal basis for $T_pM$ and $(\phi_1, \dots, \phi_n)$ is the corresponding dual basis, then the set

forms an orthonormal basis for $T_l^k(T_pM)$. In fact, the desired inner product can be described in local coordinates as

Proof. Choose $p \in M$, and find local coordinates $(x^1, \dots, x^n)$. Let $(\partial_1, \dots, \partial_n)$ denote the corresponding basis of tangent vectors, and let the corresponding dual basis be $(\mathrm{d}x^1, \dots, \mathrm{d}x^n)$. Furthermore, let $T$ denote the change of basis matrix from $(\partial_1, \dots, \partial_2)$ to $(E_1, \dots, E_n)$, so that $E_i = T_i^jE_j$. It can be easily verified that if $S = T^{-1}$, then $\phi^i = S^i_j\mathrm{d}x^j$. Now, from the assumption, we have that

Finally, observe that by the multilinearity of the tensor product,

It follows that the inner product simply decomposes as the product of the individual inner products. This is a well-defined operation, because the operation is completely determined by its values on the given basis above, which is invariant under the choice of local coordinates.

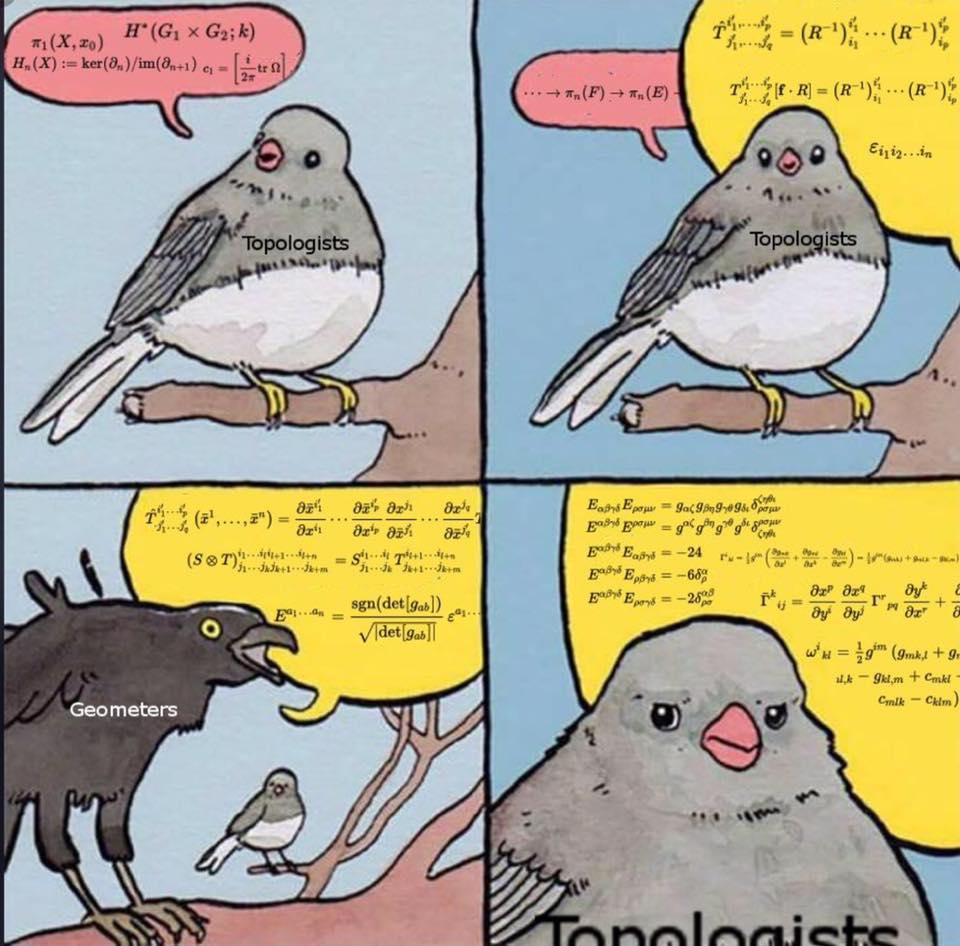

After reading through that proof, I hope you appreciate this meme as much as I do!

(Source: Mathematical Mathematics Memes)

Problems

3.10

Suppose $\tilde{M}$ and $M$ are smooth manifolds, and $\pi: \tilde{M} \to M$ is a surjective immersion.

(a) Show that any smooth vector field $W$ on $\tilde{M}$ can be written uniquely as $W = W^H + W^V$, where $W^H$ is horizontal, $W^V$ is vertical, and both $W^H$ and $W^V$ are smooth.

Proof. Let $p \in M$. Then, by the rank theorem, there exists charts $(U, \phi)$, $(V, \psi)$ containing $p$ and $\pi(p)$, respectively, such that locally, $\pi$ can be written as

where $n$ and $m$ are the dimensionalities of $\tilde{M}$ and $M$, respectively. In particular, observe that

and

Therefore, locally, the vertical space can be described as the span of $\left\{\partial/\partial x_{m + 1}, \dots, \partial/\partial x_n\right\}$. Consequently, since all component functions of $W$ are smooth, $W^V$ is smooth, and thus $W^H = W - W^V$ is smooth. The uniqueness of the decomposition follows easily from the fact that each tangent space decomposes into the orthogonal direct sum of the vertical and horizontal space.

(b) If $X$ is a smooth vector field on $M$, show that there is a unique smooth horizontal vector field $\tilde{X}$ on $\tilde{M}$, called the horizontal lift of $X$, that is $\pi$-related to $X$.

To be continued! (Last update: 02/03/2019)